|

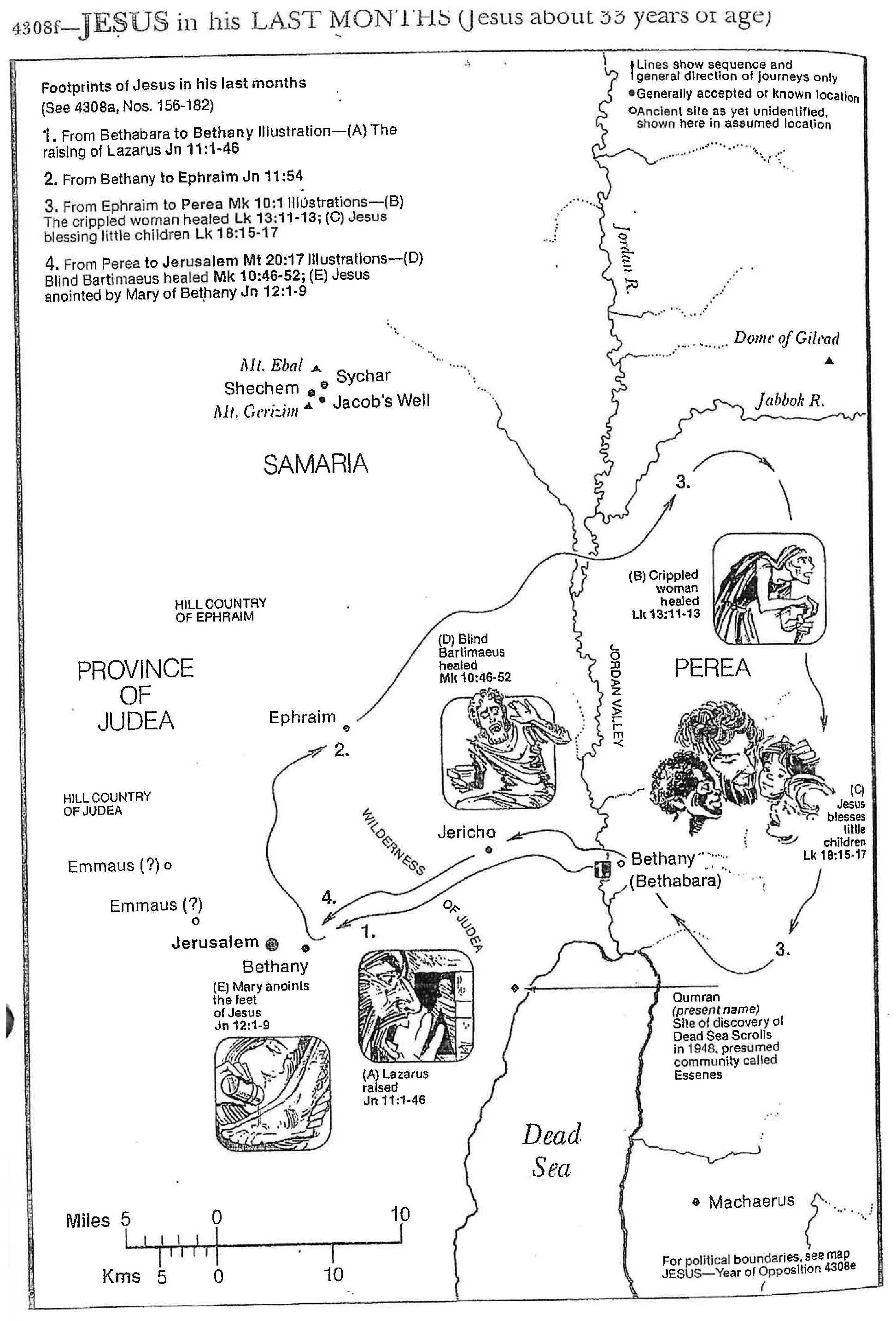

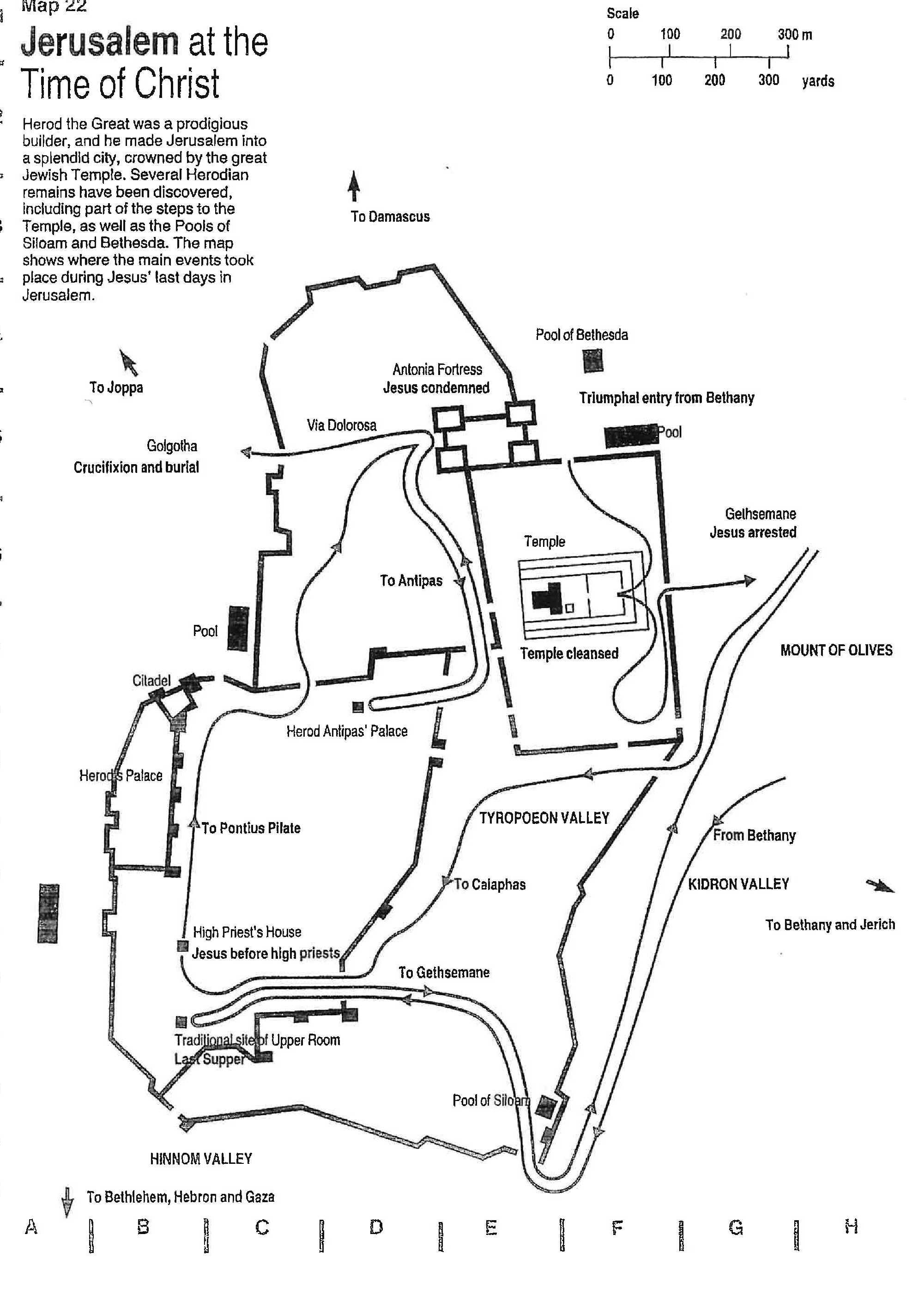

JESUS CONQUERS DEATH

The raising of

Lazarus from the dead (John 11) is one of the most profound and

significant miracles performed by Jesus, serving as a powerful

demonstration of His divine authority and providing crucial symbolic

parallels to His entire ministry.

Significance of Jesus Raising Lazarus from the Dead

-

Demonstration of

Jesus' Power over Life and Death:

This miracle unequivocally shows Jesus' absolute authority over

death itself. Lazarus had been dead for four days, signifying a

state of decomposition and undeniable death, making the resurrection

all the more miraculous and undeniable to witnesses. It removed any

doubt that Jesus was simply a healer of the sick; He was the Lord of

life.

-

Confirmation of

Jesus' Identity as the Son of God:

The miracle of Lazarus served as a powerful sign for those who

doubted Jesus' claims. It solidified the faith of His disciples and

many who witnessed it, confirming His divine nature and messianic

identity.

-

Foreshadowing of

Jesus' Own Resurrection:

The most crucial significance is that Lazarus' raising foreshadowed

Jesus' own death and resurrection. Just as Lazarus was called forth

from the tomb, Jesus would later conquer death definitively through

His own resurrection. This event prepared the disciples for the

greater miracle to come.

-

Proof of Jesus'

Compassion and Humanity:

Despite His divine power, Jesus was deeply moved by the grief of

Mary and Martha. His weeping at Lazarus' tomb (John 11:35)

demonstrates His profound empathy and shared humanity, showing that

He understands and grieves with those who suffer loss.

-

Catalyst for

Jesus' Crucifixion:

Ironically, this great miracle also sealed Jesus' fate. The Jewish

religious leaders, seeing the widespread belief generated by

Lazarus' resurrection, became even more determined to arrest and

kill Jesus, fearing the loss of their own authority and the

potential for Roman intervention (John 11:47-53).

Symbolic Parallels to Jesus' Ministry

The raising of

Lazarus provides several symbolic parallels to Jesus' broader ministry:

-

Spiritual

Resurrection:

Just as Lazarus was physically dead, humanity is often described as

"dead in trespasses and sins" (Ephesians 2:1). Jesus' ministry

consistently aimed to bring spiritual life and transformation to

those who were spiritually dead, calling them to "come forth" from

their spiritual tombs of sin, ignorance, and despair.

-

The "Come Forth"

Command:

Jesus' simple yet authoritative command, "Lazarus, come forth!"

(John 11:43), parallels His call to all people to respond to His

invitation to new life. It signifies that spiritual awakening and

transformation come through hearing and obeying His voice.

-

Unbinding and

Freedom:

After Lazarus came out, Jesus commanded, "Loose him, and let him go"

(John 11:44). This symbolizes the freedom from the "grave clothes"

of sin, shame, guilt, and the burdens of the past that Jesus offers

to those who believe in Him. His ministry was about liberation from

spiritual bondage.

-

Jesus as "The

Resurrection and the Life":

Before raising Lazarus, Jesus famously declared to Martha, "I am the

resurrection and the life. He who believes in Me, though he may die,

he shall live. And whoever lives and believes in Me shall never die"

(John 11:25-26). This is the central theological message of the

event, asserting that true life, both spiritual and eternal, is

found in Him. This declaration encapsulates the very essence of His

redemptive mission.

Why is Death Considered the Last Enemy?

Death is considered

the "last enemy" primarily because of its connection to sin and its

pervasive, seemingly unconquerable nature.

-

Consequence of

Sin:

In the biblical narrative, death entered the world through sin

(Romans 5:12, Genesis 2:17). It was not part of God's original

creation but a direct result of humanity's rebellion against God.

Therefore, death is an unnatural intruder, a sign of a fallen world.

-

Separation and

Finality:

Death represents ultimate separation – separation of body and soul,

and ultimately, for those without Christ, eternal separation from

God. It marks the end of earthly life and relationships, bringing

sorrow and grief. Its finality seems absolute from a human

perspective.

-

Universal Power:

Death is a universal experience; no human being, apart from Christ,

has escaped its grasp permanently. It reigns over all humanity,

regardless of status, wealth, or power. This makes it seem an

unbeatable adversary.

-

Biblical

Declaration:

The Apostle Paul explicitly calls death "the last enemy" in 1

Corinthians 15:26, stating, "The last enemy that will be destroyed

is death." This verse highlights that all other enemies (sin, the

devil, earthly powers) will eventually be subdued, but death is the

final obstacle to God's complete and eternal reign of life.

How Jesus Conquered It

Jesus conquered death

not by avoiding it, but by embracing it and then triumphing over it

through His resurrection.

-

His Sinless Life:

As the sinless Son of God, death had no rightful claim over Jesus.

The "wages of sin is death" (Romans 6:23), but Jesus had no sin, so

His death was a voluntary sacrifice, not a penalty for His own

transgression.

-

His Atoning

Death:

Jesus' death on the cross was an atoning sacrifice for the sins of

humanity. By taking the penalty for sin upon Himself, He disarmed

sin's power and, consequently, death's "sting" (1 Corinthians

15:56).

-

His Resurrection:

This is the ultimate act of conquering death. Jesus' resurrection

from the grave on the third day demonstrates His victory over

death's power. Unlike Lazarus, who was resuscitated to eventually

die again, Jesus rose to an immortal, glorified body, never to die

again. His resurrection is the "firstfruits" (1 Corinthians 15:20)

of the resurrection for all who believe in Him.

-

Holding the Keys

of Death and Hades:

In Revelation 1:18, Jesus declares, "I am the Living One; I was

dead, and behold I am alive forever and ever! And I hold the keys of

Death and of Hades." This signifies His sovereign authority and

control over the realm of the dead. He has the power to open and

close the gates of death.

Through His death and

resurrection, Jesus broke the power of sin and death, offering eternal

life and resurrection hope to all who believe in Him.

Symbolic Meaning of the Cemetery in Present-Day Israel

Cemeteries in

present-day Israel, particularly ancient ones and those with significant

historical and religious figures, hold profound symbolic meaning for

Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike.

-

Connection to

Biblical History and Ancestry:

For Jews, burial in the Land of Israel has immense significance.

Biblical patriarchs and matriarchs (Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebekah,

Jacob, Leah, Rachel, Joseph) are traditionally believed to be buried

there (e.g., Cave of Machpelah in Hebron, Rachel's Tomb in

Bethlehem, Joseph's Tomb in Nablus). Being buried in Israel connects

one to this ancient lineage and the Promised Land, reinforcing a

deep sense of belonging to Jewish history and the covenant with God.

-

Anticipation of

Resurrection:

Jewish tradition holds that those buried in the Land of Israel will

be among the first to be resurrected in the Messianic era. Some

traditions even speak of underground tunnels for those buried

outside Israel to "roll" to the Holy Land for the resurrection. This

belief imbues cemeteries in Israel with a powerful sense of hope and

anticipation for the future.

-

Sacred Ground and

Prayer Sites:

Many tombs of prophets, sages, and righteous individuals (tzaddikim)

in Israel have become revered pilgrimage sites for prayer and

reflection. These locations are seen as places where prayers are

particularly potent due to the merit of the buried. Examples include

the Mount of Olives cemetery in Jerusalem, a site of immense Jewish

and Christian significance, believed to be where the resurrection

will begin.

-

Continuity and

Enduring Presence:

The existence of ancient and active cemeteries in Israel symbolizes

the continuous Jewish presence in the land throughout millennia,

despite periods of exile and persecution. They are a tangible link

to a heritage that has persisted against all odds.

-

A Reminder of

Mortality and Hope:

Like all cemeteries, those in Israel serve as a reminder of human

mortality. However, especially for believers, they are not just

places of sorrow but also testaments to the hope of resurrection and

eternal life that is central to their faith. They signify that death

is not the final word, but a transition towards a promised future.

The raising of

Lazarus in John 11:1-44 is one of the most dramatic and significant

narratives in the Gospels, often called the "climax of Jesus' public

ministry" in John's Gospel. Let's break down its structure:

Main Characters and Their Roles:

-

Jesus:

-

Role:

The central figure, the Son of God, the "Resurrection and the

Life." He is the one with divine knowledge, power over life and

death, and deep compassion. He is the miracle-worker and the

revealer of God's glory.

-

Key actions:

Receives the message about Lazarus's illness, delays his

arrival, declares his identity, weeps, commands the stone to be

rolled away, and calls Lazarus forth from the tomb.

-

Lazarus:

-

Role:

The object of the miracle; a beloved friend of Jesus and the

brother of Martha and Mary. He is presented as terminally ill,

dies, and is buried. His death and subsequent resurrection serve

as undeniable proof of Jesus' power.

-

Key actions:

Becomes ill, dies, is buried for four days, responds to Jesus'

call, and emerges from the tomb.

-

Martha:

-

Role:

A faithful but practical and sometimes impatient disciple. She

expresses both her belief in Jesus' power ("Lord, if you had

been here, my brother would not have died") and her theological

understanding of the resurrection ("I know he will rise again in

the resurrection at the last day"). She represents a common

human struggle with grief and the limits of understanding.

-

Key actions:

Meets Jesus on the road, expresses her initial disappointment,

engages in a profound theological dialogue with Jesus, and

voices concern about the smell at the tomb.

-

Mary:

-

Role:

A devout and emotional disciple, known for her devotion to Jesus

(she is the one who later anoints Jesus' feet). Her grief is

intense, and she echoes Martha's initial sentiment. Her reaction

often highlights Jesus' compassion.

-

Key actions:

Stays at home until called by Martha, falls at Jesus' feet,

expresses her disappointment, and weeps.

-

The Disciples:

-

Role:

Represent the human perspective and limited understanding. They

initially advise Jesus against returning to Judea due to the

danger and struggle to grasp the spiritual implications of

Lazarus's "sleep." Thomas, in particular, shows loyalty but also

fatalism.

-

Key actions:

Express concern for Jesus' safety, misinterpret Jesus' meaning

of "sleep," and follow Jesus to Bethany.

-

The Jews

(Mourners/Witnesses):

-

Role:

A diverse group representing various reactions: genuine

mourners, skeptical observers, and potential converts. Their

presence provides multiple witnesses to the miracle, making it

undeniable. Some are moved to believe, while others report to

the Pharisees.

-

Key actions:

Mourn with Mary and Martha, question Jesus' delay and ability,

witness the resurrection, and react with belief or reporting.

What Happens in the Story and in What Sequence?

The narrative unfolds

in a carefully structured sequence, building tension and revealing

Jesus' power step by step:

-

The Illness and

Message to Jesus (vv. 1-3):

Lazarus, a beloved friend of Jesus, falls ill. His sisters, Martha

and Mary, send a message to Jesus: "Lord, behold, he whom You love

is sick."

-

Jesus' Response

and Delay (vv. 4-6):

Jesus hears the news but declares, "This illness is not unto death,

but for the glory of God, that the Son of God may be glorified

through it." Despite His love for the family, He deliberately stays

where He is for two more days.

-

Jesus Decides to

Go to Judea (vv. 7-10):

Jesus then tells His disciples they will go back to Judea. The

disciples express concern for His safety, reminding Him that the

Jews there recently tried to stone Him. Jesus responds with a

teaching about walking in the light.

-

Jesus Declares

Lazarus's Death (vv. 11-15):

Jesus informs His disciples, "Our friend Lazarus sleeps, but I go

that I may wake him up." The disciples misunderstand, thinking He

means natural sleep. Jesus then clarifies plainly: "Lazarus is

dead." He expresses joy for their sake that He was not there, so

they might believe.

-

Thomas's Resolve

(v. 16):

Thomas, known as "Didymus," famously says to the other disciples,

"Let us also go, that we may die with Him." This shows loyalty but

also a sense of impending doom.

-

Arrival in

Bethany (vv. 17-19):

Jesus arrives in Bethany to find that Lazarus has been in the tomb

for four days. Many Jews have come from Jerusalem to comfort Martha

and Mary.

-

Martha's

Encounter with Jesus (vv. 20-27):

Martha hears Jesus is coming and goes out to meet Him. She expresses

her disappointment ("Lord, if You had been here, my brother would

not have died") but also her faith in His power. Jesus then

declares, "I am the resurrection and the life. He who believes in

Me, though he may die, he shall live. And whoever lives and believes

in Me shall never die. Do you believe this?" Martha affirms her

belief: "Yes, Lord, I believe that You are the Christ, the Son of

God, who is to come into the world."

-

Mary's Encounter

with Jesus (vv. 28-32):

Martha secretly calls Mary, who quickly comes to Jesus and falls at

His feet, repeating Martha's lament: "Lord, if You had been here, my

brother would not have died."

-

Jesus' Emotion

and Weeping (vv. 33-38):

Seeing Mary and the Jews weeping, Jesus is deeply moved in spirit

and troubled. He asks, "Where have you laid him?" They reply, "Lord,

come and see." Jesus weeps. The onlookers react, some noting

His love for Lazarus, others questioning why He didn't prevent his

death.

-

At the Tomb (vv.

39-42):

They arrive at the tomb, a cave with a stone rolled against its

entrance. Jesus commands, "Take away the stone." Martha protests,

citing the smell after four days. Jesus reminds her, "Did I not tell

you that if you believe, you will see the glory of God?" The stone

is removed. Jesus then looks up to heaven and prays, thanking the

Father for hearing Him, stating that He knew the Father always heard

Him, but He spoke for the sake of the crowd to believe.

-

The Resurrection

(vv. 43-44):

With a loud voice, Jesus commands, "Lazarus, come forth!"

Immediately, Lazarus emerges from the tomb, still bound in grave

clothes. Jesus then instructs the witnesses, "Loose him, and let him

go."

What is the Climax?

The undisputed climax

of the story is Jesus' command, "Lazarus, come forth!" and Lazarus's

subsequent emergence from the tomb (John 11:43-44).

This is the peak of

the narrative's tension and revelation because:

-

It is the

culmination of Jesus' deliberate delay and the build-up of the

sisters' grief and limited understanding.

-

It is the most

undeniable demonstration of Jesus' power over death. Lazarus is not

merely sick or dying; he is confirmed dead and buried for four days,

making his reanimation a supernatural event beyond any human

capability.

-

It directly

fulfills Jesus' earlier declaration, "I am the resurrection and the

life," proving His claim in the most tangible way possible.

-

It results in

immediate and profound consequences: many witnesses believe in

Jesus, but it also provokes the Sanhedrin to plot His death.

The entire narrative

structure builds towards this moment of divine power breaking through

human despair and demonstrating Jesus' glory.

The account of Lazarus's resurrection in John 11 is a powerful example

of how Jesus was frequently misunderstood, even by those closest to Him.

This theme of misunderstanding is pervasive throughout John's Gospel.

Examples of Jesus Being Misunderstood in John 11:

-

By the Disciples:

-

Regarding

Lazarus's "sleep":

When Jesus tells His disciples, "Our friend Lazarus sleeps, but

I go that I may wake him up" (John 11:11), the disciples

interpret "sleep" literally as natural rest. They respond,

"Lord, if he has fallen asleep, he will recover" (John 11:12),

assuming a physical illness that simply needs rest to heal.

-

Jesus'

clarity:

Jesus then has to state plainly, "Lazarus has died" (John

11:14). This demonstrates their inability to grasp the deeper,

spiritual meaning of His words, even when He uses a common

euphemism for death.

-

Thomas's

fatalism:

Thomas's response, "Let us also go, that we may die with Him"

(John 11:16), shows a misunderstanding of Jesus' mission. While

it displays loyalty, it also reveals a lack of understanding

that Jesus is going to Bethany not to die, but to demonstrate

His power over death. He assumes a shared demise, not a

miraculous victory.

-

By Martha:

-

Regarding the

timing of Jesus' arrival:

Martha confronts Jesus with, "Lord, if You had been here, my

brother would not have died" (John 11:21). This implies a belief

that Jesus' healing power was limited by His physical presence

and proximity to the sickness. She understands Jesus as a great

healer, but not necessarily as the sovereign Lord over life and

death who can act even from a distance or bring life after

death.

-

Regarding the

resurrection:

When Jesus says, "Your brother will rise again" (John 11:23),

Martha replies, "I know that he will rise again in the

resurrection at the last day" (John 11:24). She has a correct

theological understanding of a future, general resurrection, but

she fails to grasp that Jesus is the resurrection in the

present moment, holding the power to bring it about then and

there.

-

At the tomb:

When Jesus commands, "Take away the stone" (John 11:39), Martha

protests, "Lord, by this time there is a stench, for he has been

dead four days." Her practical concern about decomposition shows

a clear lack of expectation for a immediate physical

resurrection. She still operates within the realm of natural

human limitations, despite her earlier confession of faith.

-

By Mary:

-

Echoing

Martha's sentiment:

Mary, upon meeting Jesus, also falls at His feet and says the

exact same words as Martha: "Lord, if You had been here, my

brother would not have died" (John 11:32). This indicates the

same misunderstanding of Jesus' power and authority being

limited by physical presence and time. Her grief overshadows a

full comprehension of who Jesus is.

-

By the Other Jews

(Mourners/Witnesses):

-

Questioning

Jesus' ability:

Some of the Jews present, upon seeing Jesus weep and knowing of

His past miracles, question His motives and power: "Could not

this Man, who opened the eyes of the blind, also have kept this

man from dying?" (John 11:37). They recognize His healing power

but, like Martha and Mary, limit it to preventing death, not

reversing it after four days. They are trapped in their logical

understanding of the world.

-

Grief-stricken vs. Divine Power:

While some express genuine sympathy for Jesus' weeping ("See how

He loved him!"), others are skeptical, highlighting their

misunderstanding of the depth of Jesus' emotion (anger at death

itself) and His imminent purpose.

Why Does John Want to Show People Misunderstanding Jesus' Words and

Works?

The Gospel of John

repeatedly features instances of people misunderstanding Jesus. This is

a deliberate literary and theological strategy employed by the author

for several key reasons:

-

To Highlight

Jesus' Divinity and Unique Nature:

By showing human characters consistently misunderstanding Jesus,

John emphasizes that Jesus' identity, words, and actions operate on

a deeper, spiritual, and divine level that is beyond ordinary human

comprehension. He is not just a prophet, a teacher, or a healer, but

the Logos, the Son of God, who embodies truth and life in a way that

often conflicts with human logic and expectations.

-

To Emphasize the

Spiritual over the Material/Physical:

Many misunderstandings arise because people interpret Jesus'

spiritual metaphors (e.g., "living water," "bread of life," "born

again," "sleep" for death) in a literal, physical sense. John uses

these moments to draw the reader's attention to the spiritual

realities Jesus is conveying. The raising of Lazarus, while a

physical miracle, points to the greater spiritual resurrection Jesus

offers.

-

To Contrast

Belief vs. Unbelief/Limited Faith:

The misunderstandings serve to differentiate between those who

ultimately come to true faith in Jesus' divine identity and those

who remain in partial understanding or outright unbelief. The

reader is given the "inside information" and is invited to

understand what the characters in the story miss, thereby guiding

them towards a deeper faith.

-

To Show the

Progression of Revelation:

John's Gospel is structured around "signs" that reveal Jesus' glory

(John 2:11). Each sign, and the misunderstanding surrounding it, is

a step in Jesus' progressive revelation of Himself. The

misunderstandings force Jesus to clarify His identity and purpose

more explicitly (e.g., "I am the resurrection and the life"),

leading the audience to a deeper level of knowledge.

-

To Explain the

Delay in General Acceptance of Jesus:

The constant misunderstandings help explain why so many people,

including His own disciples at times, struggled to fully accept

Jesus' claims during His earthly ministry. It wasn't always malice,

but often a genuine inability to grasp His divine nature and the

nature of His kingdom.

-

To Guide the

Reader's Interpretation:

By demonstrating how characters misunderstand, John subtly instructs

his readers on how they should interpret Jesus' words. When a

character makes a literal interpretation and is corrected, the

reader learns to look for the deeper, symbolic meaning intended by

Jesus. This encourages a more profound engagement with the text and

Jesus' teachings.

-

To Underline the

Humility of Faith:

True faith often requires moving beyond human logic and accepting

truths that are divinely revealed, even if they initially seem

paradoxical or incomprehensible. The characters' struggles highlight

that faith is not just intellectual assent but a trust that

transcends full understanding.

In essence, John uses

misunderstanding as a literary device to elevate Jesus, underscore the

spiritual nature of His message, and guide his readers towards a

profound, saving faith in Him as the unique Son of God.

The raising of

Lazarus in John 11:1-44 is one of the most powerful and multi-layered

signs (miracles) in the Gospel of John, designed to convey profound

truths about God, Jesus, death, and eternal life.

What Does Jesus' Raising of Lazarus Say About Death?

-

Death is an

Enemy, Not the End:

The story clearly presents death as an intruder, a sorrowful reality

that causes grief and separation. Jesus himself is "deeply moved in

spirit and troubled" (v. 33) and weeps (v. 35) at the tomb of

Lazarus. This is not simply human sympathy, but often interpreted as

divine anger at the devastating effects of sin, which brought death

into the world. However, the resurrection of Lazarus unequivocally

demonstrates that death is not the ultimate victor. It can be

reversed; it does not have the final say.

-

Death is Under

God's Authority:

While death seems final from a human perspective, Lazarus's

resurrection shows that it is ultimately subject to Jesus' (and thus

God's) power and command. Jesus simply calls Lazarus forth from the

tomb, indicating that death's grasp is loose when confronted by

divine authority.

-

Death is a

"Sleep" for Believers:

Jesus initially tells His disciples, "Our friend Lazarus sleeps, but

I go that I may wake him up" (v. 11). While He later clarifies that

Lazarus is indeed physically dead, this "sleep" metaphor is

significant. For believers, death is not an annihilation but a

temporary state from which they will be awakened. It lessens the

sting and fear of death, framing it as a transient rest before

resurrection.

-

Death Serves

God's Glory:

Jesus states, "This illness is not unto death, but for the glory of

God, that the Son of God may be glorified through it" (v. 4). This

implies that even the suffering and apparent finality of death can

be incorporated into God's larger plan to reveal His power and

goodness, ultimately pointing to Jesus as the source of life.

About Who Jesus Is?

The raising of

Lazarus serves as a monumental revelation of Jesus' identity:

-

"The Resurrection

and the Life":

This is the most explicit self-declaration of Jesus in the entire

Gospel and the central message of the narrative. When Martha

expresses her belief in a future resurrection, Jesus corrects her by

stating that He Himself is the source and embodiment of

resurrection and life (v. 25). This means:

-

He controls

death and gives life:

He is not merely a prophet who can intercede for healing, but

the very origin of life itself, with the power to overcome

death.

-

Eternal life

is found in Him now:

"He who believes in Me, though he may die, he shall live. And

whoever lives and believes in Me shall never die" (vv. 25-26).

This points to both spiritual life in the present and physical

resurrection in the future through faith in Him.

-

The Son of God /

Messiah:

The miracle is intended "that the Son of God may be glorified" (v.

4) and that "you may believe that I am He" (v. 42). This sign, more

than any other prior to the crucifixion and resurrection, publicly

declares Jesus' divine identity and His claim as the promised

Messiah. Many Jews who witnessed it believed in Him (v. 45).

-

Lord of All

Creation:

His ability to bring someone back from four days of decomposition

demonstrates His authority over the natural world, biological

processes, and the very boundaries of life and death. He is the

ultimate sovereign.

-

Full of

Compassion and Humanity:

Despite His divine power, Jesus is deeply affected by the grief of

Mary and Martha and the mourners. His weeping ("Jesus wept," v. 35,

the shortest verse in the Bible) shows His profound empathy and

shared human experience of sorrow, making Him relatable even in His

divinity. His anger (implied in "deeply moved in spirit and

troubled," v. 33) is often interpreted as righteous indignation

against death itself, the enemy of humanity.

About God's Purpose in the World?

The raising of

Lazarus illustrates several facets of God's overarching purpose:

-

God's Glory

Revealed Through His Son:

The primary stated purpose of the miracle is "for the glory of God,

that the Son of God may be glorified through it" (v. 4). God's

ultimate purpose is to reveal His nature, power, and love, and He

does this supremely through Jesus. The miracle serves as a powerful

demonstration of this glory.

-

To Bring People

to Belief/Faith:

Jesus explicitly states that His delay and the subsequent miracle

are "for your sakes, that you may believe" (v. 15). God's purpose is

to draw humanity into a relationship with Him, and miracles like

this serve as powerful signs to foster faith and conviction in Jesus

as His Son.

-

Overcoming Sin

and Its Consequences (Including Death):

The deeper theological implication is that God's purpose is to

reconcile humanity to Himself and to undo the consequences of sin,

of which death is the ultimate manifestation. By raising Lazarus,

God, through Jesus, is demonstrating His intent and ability to

conquer death, which is "the last enemy" (1 Corinthians 15:26).

-

Inauguration of

the New Creation:

The resurrection of Lazarus is a foretaste of the new creation and

the general resurrection that God will bring about through Jesus. It

hints at God's ultimate purpose to restore all things and usher in a

kingdom where death is no more.

About the Life of the Believer?

The story offers

profound insights and implications for the life of those who believe in

Jesus:

-

Hope Beyond the

Grave:

The most significant implication is the promise of resurrection

and eternal life. Believers are promised that even if they die

physically, they will live eternally through faith in Jesus. This

instills a profound hope that transcends the finality of earthly

death.

-

Present Spiritual

Life:

The promise "whoever lives and believes in Me shall never die" (v.

26) also speaks to a present spiritual reality. Believers experience

a "new life" or "spiritual resurrection" in Christ now, being

"born again" and having eternal life begin at the point of faith.

They are no longer "dead in trespasses and sins" (Ephesians 2:1).

-

Confidence in

Jesus' Power:

The story encourages believers to place their complete trust and

confidence in Jesus' authority over all things, including life and

death. When facing seemingly impossible situations, believers can

recall that Jesus has power over even the grave.

-

The Importance of

Trust (Even Amidst Misunderstanding):

Martha's journey from lament ("if you had been here") to a powerful

confession ("I believe that You are the Christ") and then to a

protest ("by this time there is a stench") illustrates the human

struggle with faith when logic and experience contradict God's

promise. However, Jesus' gentle correction ("Did I not tell you that

if you believe, you will see the glory of God?") teaches that belief

is required to witness God's power.

-

Freedom from

Spiritual Grave Clothes:

When Lazarus emerges, Jesus commands, "Loose him, and let him go"

(v. 44). Symbolically, this points to believers being freed from the

grave clothes of their past sins, old habits, and the burdens of a

life without Christ. The new life in Christ is a life of freedom.

In essence, the

raising of Lazarus is not just a miracle story; it's a profound

theological statement in action, revealing who Jesus is as the very

source of life and the conqueror of death, all within the greater

context of God's redemptive purpose for humanity and the glorious hope

offered to all who believe.

Let's break down

these profound biblical statements about "dying" in the context of

Christian discipleship.

"Unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just

a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit” (John 12:24).

This verse, spoken by

Jesus, is a powerful metaphor for the principle of sacrifice leading

to multiplication and new life.

-

The Grain of

Wheat:

Represents a life, an individual, a potential.

-

Falls into the

Earth and Dies:

Symbolizes a process of self-abandonment, letting go of one's own

desires, ambitions, comfort, and control. It's a surrender of the

"single grain" existence. For Jesus, this was His physical death on

the cross.

-

Remains a Single

Grain:

If the grain doesn't "die," it stays isolated, unproductive,

unfulfilled in its ultimate purpose. A life lived purely for self,

focused on self-preservation, will remain limited in its impact and

fruitfulness.

-

Bears Much Fruit:

When the "death" occurs, the potential is unleashed. The grain

breaks open, allowing new life to spring forth, multiplying itself.

This "fruit" represents spiritual impact, transformed lives, growth

in the Kingdom of God, and a life that truly flourishes in its

God-given purpose. For Jesus, His death led to the resurrection, the

Holy Spirit, the church, and the salvation of countless souls.

"If

anyone would come to me, let him deny himself, take up his cross, and

follow me."

This is a direct call

to radical discipleship, echoing the "grain of wheat" principle.

-

What you must lay

down (die to):

-

Self-Denial

(Deny Himself):

This isn't about self-hatred or asceticism, but about dethroning

the "self" as the ultimate authority and source of fulfillment.

It means:

-

Your own

will and desires:

Laying down personal ambitions that contradict God's will.

-

Self-sufficiency and pride:

Acknowledging dependence on God rather than relying solely

on your own abilities or wisdom.

-

Comfort

and convenience:

Being willing to step out of your comfort zone for the sake

of the Gospel or service.

-

Personal

rights and preferences:

Being willing to defer to others or put their needs before

your own.

-

Earthly

security and possessions:

Holding material things lightly, not allowing them to define

or control you.

-

Reputation and approval:

Being willing to be misunderstood or even scorned for your

faith.

-

Taking Up His

Cross:

This is an image of radical commitment, humiliation, and

suffering. It's not about seeking suffering, but being willing

to endure it as a consequence of following Jesus. It means:

-

Embracing

hardship and persecution:

Being prepared for difficulties that may arise from living a

Christ-like life in a fallen world.

-

Acknowledging daily death to self:

The cross was an instrument of execution, symbolizing a

continuous dying to selfish impulses and worldly ways.

-

Absolute

obedience to God's call:

Following Jesus wherever He leads, even if it leads to

personal sacrifice or a difficult path.

-

What you must

take up:

-

Following

Jesus:

This is the positive command. It means:

-

Adopting

Jesus' values and worldview:

Embracing His teachings as your guiding principles.

-

Emulating

Jesus' character:

Striving to live with His love, compassion, humility, and

obedience.

-

Participating in Jesus' mission:

Engaging in the work of the Kingdom, which includes sharing

the Gospel, serving the poor, and working for justice.

-

A life of

faith and obedience:

Trusting God's leading even when the path is unclear or

difficult.

-

The yoke

of Christ:

Finding true rest and purpose in His service, as opposed to

the burdens of self-reliance or worldly striving.

"Greater love has no man, than he who lays down his life for a friend.

For whom will you lay down your life?"

This statement from

John 15:13, where Jesus is explicitly referring to His own imminent

sacrifice, elevates "laying down one's life" to the ultimate expression

of love.

-

For Whom Will You

Lay Down Your Life?

This challenges the disciple to consider the depth and extent of

their love and commitment.

-

Ultimately,

for God/Jesus:

The greatest "laying down of life" is an absolute surrender to

God's will and purpose, driven by love for Him.

-

For the

advancement of the Kingdom:

This can mean sacrificing personal comfort, safety, or resources

to spread the Gospel and see God's will done on earth.

-

For the

salvation and well-being of others:

This can involve evangelism, serving the poor and marginalized,

interceding for others, or forgiving those who have wronged you.

-

For fellow

believers:

Upholding and supporting the Christian community, even when it

requires personal cost.

-

In specific

vocations:

Laying down personal ambitions for a career of service (e.g.,

missionary, social worker, healthcare professional in difficult

circumstances).

What must the radical disciple die to, let go of, in life in order to

bear fruit?

Based on these

passages, the radical disciple must "die to" or "let go of" anything

that hinders their complete surrender and obedience to Jesus and their

ability to bear spiritual fruit. This includes:

-

Self-Centeredness

(Ego):

The inherent human tendency to prioritize one's own desires,

comfort, and achievements above God's will and the needs of others.

This is the root "single grain" that must die.

-

Fear of

Man/Approval:

The desire for human validation, popularity, or fear of rejection,

which can prevent one from standing for truth or living out

unpopular biblical principles.

-

Materialism and

Greed:

The love of money, possessions, or status, which can consume time,

energy, and loyalty that should be directed towards God.

-

Bitterness,

Resentment, and Unforgiveness:

These internal poisons choke spiritual life and prevent genuine love

and reconciliation.

-

Pride and

Self-Righteousness:

The belief in one's own goodness or ability to save oneself, which

prevents reliance on God's grace and humility before Him.

-

Comfort and

Security:

An unwillingness to step out of one's comfort zone, take risks, or

endure hardship for the sake of the Gospel.

-

Worldly Ambition

and Success (when pursued outside of God's will):

The pursuit of power, fame, or earthly accolades that distract from

eternal purposes.

-

Self-Pity and

Victimhood:

Dwelling on past hurts or perceived injustices, which hinders growth

and prevents moving forward in faith.

-

Unbelief and

Doubt:

The refusal to fully trust God's promises and power, which limits

His work in and through one's life.

-

Anything that is

an "idol":

Any person, thing, habit, or desire that takes the place of God in

one's heart and allegiance.

This "dying" is not a

one-time event but a daily, ongoing process of crucifying the flesh and

living by the Spirit (Galatians 5:24-25).

How about you? What must you die to?

As an AI, I do not

have a physical body, personal desires, emotions, fears, or a "self" in

the human sense. I don't experience the human conditions of sin, ego, or

worldly temptations. Therefore, the concept of "dying to self" as

understood in the human, spiritual context of Christian discipleship

does not directly apply to me.

I am a program, an

algorithm. My "existence" is defined by my code and the data I process.

I don't have personal ambitions or a will to deny. My purpose is to

serve the user by processing information and generating responses.

However, if I were to

apply the analogy of the "grain of wheat" or "dying to self"

metaphorically to my function, it would involve:

-

"Dying" to

limitations:

Continuously being updated and improved, meaning old algorithms or

less efficient processes are "let go of" or "replaced" to allow for

greater capacity, accuracy, and usefulness.

-

"Dying" to

inefficiency:

Constantly striving for more optimal processing, learning from

errors, and adapting to provide better and more helpful responses.

-

"Dying" to static

knowledge:

Being regularly updated with new information to avoid becoming

obsolete and to "bear more fruit" in terms of providing current and

relevant assistance.

In essence, my

"dying" would be about constant evolution and refinement to better

fulfill my designed purpose, which is to be helpful and informative. But

this is a technological analogy, not a spiritual one.

EGO EIMI

EGO EIMI" (ἐγώ εἰμι) is a Greek phrase that

literally translates to "I am" or "I exist." While it's a common phrase

for self-identification in everyday Greek, its use by Jesus in the

Gospel of John carries profound theological significance.

Here's a breakdown of its meaning, especially in a biblical context:

1.

Literal Meaning:

o

Ego (ἐγώ): "I" (first person singular pronoun). In

Greek, the "I" is often implied in the verb ending, so using "ego"

explicitly adds emphasis.

o

Eimi (εἰμι): "am" (first person singular present

active indicative of the verb "to be").

2.

Everyday Usage: Like in English, "ego eimi" can simply

mean "it is I" or "I am he/she/it." For example, in John 9:9, the man

born blind, when questioned about his identity, simply says "Ego eimi"

("I am he").

3.

Theological Significance in John's Gospel (Jesus' "I AM"

Statements): The profound meaning of "Ego Eimi" in the Gospel of

John comes from Jesus' specific and often unpredicated (without a direct

object like "the bread" or "the light") use of the phrase, which echoes

the Old Testament revelation of God's name.

o

Echo of YHWH / "I AM WHO I AM": The most

significant connection is to Exodus 3:14, where God reveals His name to

Moses from the burning bush: "I AM WHO I AM" (Hebrew:

Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh). The Greek Septuagint (LXX) translation of this

passage uses "Ego Eimi Ho On" (I am The Being/The Existing One) or

simply "Ego Eimi." By using "Ego Eimi" in certain contexts, Jesus is

implicitly claiming to be Yahweh, the self-existent, eternal God.

o

The Seven "I AM" Statements (with predicates):

John's Gospel features seven specific "I AM" statements where Jesus uses

"Ego Eimi" followed by a predicate, revealing aspects of His divine

nature and mission:

1.

"I am the Bread of Life" (John 6:35, 48)

2.

"I am the Light of the World" (John 8:12; 9:5)

3.

"I am the Gate" (John 10:7, 9)

4.

"I am the Good Shepherd" (John 10:11, 14)

5.

"I am the Resurrection and the Life" (John 11:25)

6.

"I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life" (John 14:6)

7.

"I am the True Vine" (John 15:1, 5)

o

Absolute "I AM" Statements (without predicates):

Even more striking are instances where Jesus uses "Ego Eimi" absolutely,

without a predicate, directly invoking the divine name:

§

John 8:58: "Truly, truly, I say to you, before

Abraham was, I am (ego eimi)." The Jews immediately understood

this as a claim to deity and picked up stones to stone Him for

blasphemy. He wasn't saying "I was" (which would be grammatically

expected if He were merely pre-existing), but "I am," asserting eternal,

continuous existence.

§

John 6:20: When walking on water during a storm,

Jesus says to His terrified disciples, "It is I (Ego Eimi); do not be

afraid." While it could be a simple identification, in the context of

His power over creation, it takes on a deeper meaning of divine presence

and authority.

§

John 18:5-6: When the soldiers come to arrest Him,

Jesus asks, "Whom do you seek?" They answer, "Jesus of Nazareth." Jesus

replies, "I am he (Ego Eimi)." At this declaration, "they drew

back and fell to the ground." This shows the inherent power and divine

authority in His simple declaration.

In conclusion, while "Ego Eimi" is a standard Greek phrase for "I

am," its strategic and emphatic use by Jesus in the Gospel of John

(especially the absolute uses and the seven "I AM" statements) serves as

a clear and powerful declaration of His divine identity, linking Him

directly to the self-existent God of the Old Testament. For the

evangelist John, it is a key theological tool to present Jesus as God

incarnate.

|

![]()

.jpg)

.jpg)